Header start

- Home

- Press Releases Index

-

Press Releases

Press Releases

Pancreatic cancers change identity as they transform into aggressive types

― an organoid study

Experiments with patient-derived organoids highlight the influence of environmental conditions on cell identity

September 5, 2024

Keio University School of Medicine

Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest cancers worldwide. A promising technology poised to advance treatment is organoids, the miniature laboratory versions of a patient’s tissues and organs. These are valuable tools for studying causal relationships between genes and phenotypes, as well as with treatments and outcomes.

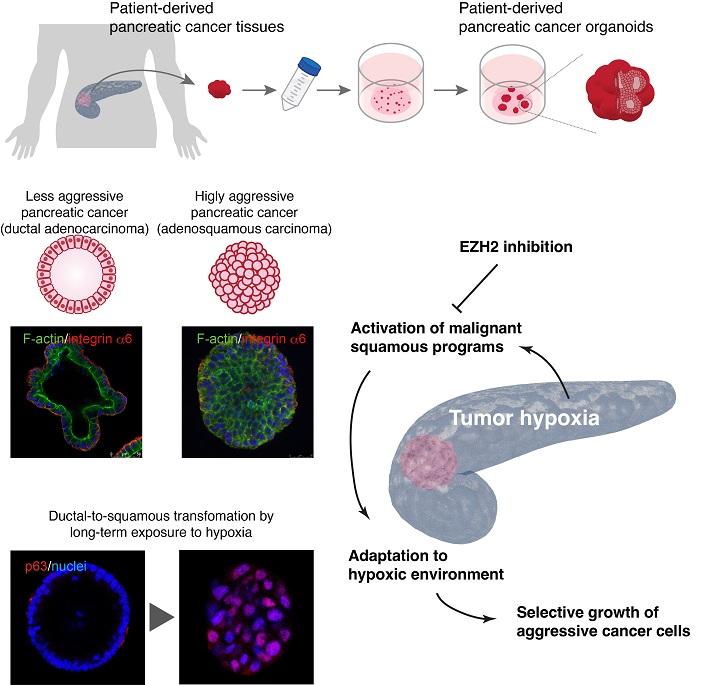

A new organoid study shows that low-oxygen environments transform pancreatic cancer cells into aggressive pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma (PASC), a rare subtype that morphologically resembles cells in the esophagus and trachea. Furthermore, the study found that a widely studied drug shows promise in reversing the molecular changes that make tumor cells more aggressive.

Changing identities

In contrast to other commonly diagnosed cancers like colorectal and lung cancer, the 5-year survival rate after diagnosis for pancreatic cancer is alarmingly low, at 8.5% in Japan. "Only the fortunate few who happen to receive an early diagnosis and undergo surgery survive pancreatic cancer. While research in colorectal and lung cancers have extended life expectancy in the order of several years, pancreatic cancer treatment is still at a stage where a combination of the latest therapies only gives patients a few additional weeks," says Professor Toshiro Sato, Keio University School of Medicine. Identity changes in pancreatic cancer cells can contribute to their aggressiveness. About 10% of pancreatic cancers involve PASC, a pathology originating from ductal cells that begin to resemble squamous cells, a type of epithelial cell found in the esophagus and trachea. This identity shift enables the cancer cells to thrive in an environment where they otherwise would not.

Survival without oxygen

To test whether the same applied to humans, Sato's team tried to make PASC from scratch using normal pancreas organoids and gene engineering technology. Disabling KDM6A, a histone modification gene involved in epigenetic regulation of gene expression, and GATA6, a gene involved in pancreas development, made less aggressive pancreatic cancer cells transform into PASC-like cells. However, a previous study revealed that not all PASC-like cells had mutations to KDM6A. Based on a recent study showing that oxygen is crucial for KDM6A to function, the team exposed pancreatic cancer organoids to low-oxygen conditions. After two months, the organoids began to resemble PASC, suggesting that low-oxygen environments play a significant role in driving the transformation.

The role of low oxygen in changing cell identity partly explains the high fatality rate in pancreatic cancer. Many cancer tissues have extra blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients, fueling cell growth, whereas blood vessels are known to be very scarce in pancreatic cancers. "The reason why pancreatic cancers became so aggressive without the extra oxygen and nutrients was unclear, but the current study elucidates the genetic mechanisms behind how they transform under low oxygen," says Sato.

Targeting the epigenome

The study also showed that a class of drugs called EZH2 inhibitors, which block the addition of epigenetic markers to the genome, can reverse the molecular changes that trigger the transformation into PASC-like cells. "The outcomes of this study suggest that drugs targeting such processes could be highly effective against other cancers that become aggressive due to identity changes," says Sato.

Sato says that an important next step would be to collaborate with applied research teams to validate the effectiveness of combining EZH2 inhibitors with other drugs. Furthermore, Sato's research now focuses on studying the early stages of pancreatic cancer development. "In pancreatic cells that become cancerous, what happens before mutations occur? This knowledge could help with prevention," says Sato.

|

Authors |

|

|

Title of original paper |

Wnt-deficient and hypoxic environment orchestrates squamous reprogramming of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

|

| Journal |

|

|

DOI |

|

|

Affiliations |

|

Dr. Toshiro Sato is a Professor in the Department of Integrated Medicine and Biochemistry at Keio University School of Medicine, Japan. He received his MD and PhD from Keio University and developed an organoid culture system for adult intestinal stem cells during his postdoctoral research stint at Hubrecht Institute. In 2011, Prof. Sato set up his own laboratory at Keio University, with research focused on the modeling of human gastrointestinal diseases. Prof. Sato has published over 100 research papers and has also been honored with Japan's Inoue Research Award.

Professor Toshiro Sato

Department of Integrated Medicine and Biochemistry, Keio University School of Medicine

E-mail: t.sato@keio.jp

Footer start

Navigation start