Header start

- Home

- Keio Times Index

- Keio Times

Content start

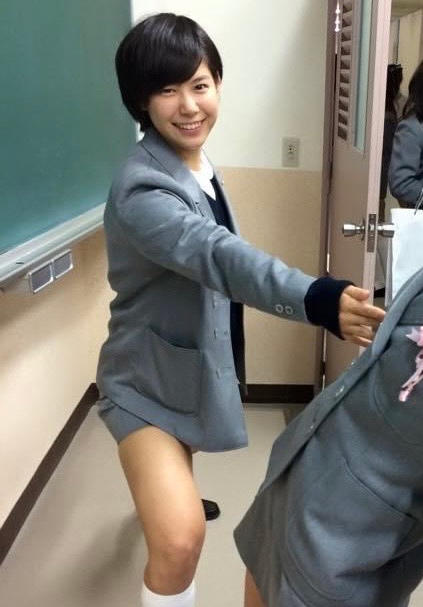

Setbacks and Struggles: How Adversity Shaped a Fencing Champion

Karin Miyawaki

Graduate of the Faculty of Economics

June 30, 2025

Beating the Older Boys at Fencing

- Congratulations on winning the bronze medal in the Women's Foil Team event at the Paris Olympics. How did you spend your time after the tournament?

Thank you very much. After receiving the medal, I returned to Japan right away and fully enjoyed my time off through the end of August. However, with the All-Japan Championships in Shizuoka scheduled for mid-September, I resumed training on September 1. I currently train daily across two two-and-a-half-hour sessions, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. I will be traveling globally until July, maintaining a pace of about one competition per month, starting with Tunisia in North Africa, followed by Europe, Asia, and Central and South America.

- Could you tell us how you first got into fencing?

It all started when my older sister said she wanted to try kendo. There wasn't a kendo dojo nearby, but there was a fencing school around the corner. My mother and sister shrugged, saying fencing was the "kendo of the West." And so my sister started taking lessons (laughs). As a kindergartener, I would tag along to my sister's practices every week. One day, the coach invited me to try, too. I had always wanted to try fencing for myself, watching my sister as she practiced, and I guess the teacher must have noticed.

Once I started, I immediately found it fascinating. My personality suited individual sports more than team ones, and my competitive nature probably helped. I could tell I was improving quickly. It was so much fun—and so gratifying—to be able to beat older boys who were much taller than me.

- You won a national tournament in fourth grade and started competing internationally in middle school. People must have had high expectations for you as a fencer. How did you feel about all that personally?

I was completely crazy about fencing, and winning competitions brought me the greatest joy. But if you asked whether I had Olympic aspirations in elementary or junior high school, the answer would be no. I also enjoyed studying at school.

A major turning point came in my first year of high school, when I met Yuki Ota, Japan's first Olympic silver medalist in fencing. He asked me in detail about my goals as an athlete, including the possibility of competing in the Olympics. At the time, I wasn't serious about joining the Olympics, so his question caught me off guard. But looking back, that conversation with Ota-san helped me make a decision about my future aspirations for fencing. I realized that no matter how hard I studied, I probably wouldn't become the best in the world at something. But with fencing, that dream seemed possible. In my second year of high school, I began to focus more on fencing than ever before. I set a clear goal: to represent Japan at the 2016 Rio Olympics.

Overcoming Two Major Setbacks

Before Reaching Her Olympic Goal

- What kind of student were you in high school?

I was pretty good at math and science, although my focus was definitely on fencing. I made a lot of friends, and every day felt fun and bright. Back then, we believed that we were the center of the world and that anything was possible. I'm still in touch with many of my friends from high school. Many of them came to the Paris Games to cheer me on, and I was so glad I could share the joy of winning a medal with them.

- You chose to study at the Faculty of Economics.

Yes, I did consider the Faculty of Science and Technology, but I realized that it would be difficult to manage my competitions and training for the Olympics while juggling time-intensive classes and research. Among the liberal arts options, I chose economics because it offered a more analytical and scientific approach. I joined the Keio Fencing Club and have fond memories of helping the team get promoted to the top division of the Kanto Collegiate Fencing League during my sophomore year. I have to confess that I wasn't your typical college student. I spent four to six months of the year traveling overseas for international fencing competitions.

- You achieved remarkable results at university, including winning the Junior World Cup in the women's individual foil event, but unfortunately you didn't make the Japanese team for the Rio Olympics.

Competing in the Olympics was my ultimate goal as a fencer, so not being selected was a huge setback. It was difficult to recover emotionally, but with the support of those around me, I gained a renewed focus. I went on to win a team gold medal at the Asian Games, kindling my motivation to train for the Tokyo Olympics. However, after graduating, I struggled to perform at the level that I'd hoped to and had to endure the disappointment of missing Olympic selection once again. Looking back, it was a truly painful time. The COVID-19 pandemic delayed the Games by a year, and athletes faced widespread criticism. I had only graduated from college about two years prior, and I was considering giving up the idea of living as an athlete and going down a different path. After what I call my "blank year," I returned to the world of fencing thanks to my friends on the Tokyo Olympic team, many of whom I had competed with before. I asked myself what I truly wanted to do, what I could devote my whole heart to, and the answer was clear: I wanted to keep fencing. It wasn't a decision made out of despair after failing to qualify. I chose, with a clear mind, to return to my original dream of competing as an Olympic athlete. I told myself that by the time the Paris Olympics came around after Tokyo, I would still only be 27. That's still a perfectly competitive age for an athlete. I knew I couldn't quit—not then. And at last, I was able to move forward.

- That was around the time you appeared on Nippon TV's quiz show "Are you smarter than a 5th grader?" and you became famous overnight for winning the 3 million yen grand prize.

After failing to qualify for the 2020 Tokyo Games, I found myself unemployed. I competed in 10 international events annually, which cost about 3 million yen in total. When I realized the prize money matched those costs, I applied as a "fencing athlete aiming for the Olympics" and was selected to go on the show. Some of the questions on the show related to my travel experiences, which helped me along the way, and I managed to answer every single one correctly. After that, I joined Mitsubishi Electric Corporation as a company-sponsored athlete, where I've remained since.

- And finally, in 2024, you were selected for the Paris Olympics. That must have been a dream come true.

Yes, it was. The results from April to March of the previous year are considered during selection for the national team, so I was very mindful of my performance throughout that season. The national team isn't announced until May, just two months before the Games, so I was on edge the whole time. I never felt as relieved as when I found out I'd compete in both the team and individual events. In that moment, I was so glad I kept fencing. The other members of Japan's women's foil team were both my rivals in domestic competitions and my teammates at the Ajinomoto National Training Center—we trained side by side and grew stronger together.

Eyes on the Prize:

Individual and Team Gold in Four Years

- The head coach of the women's foil team is Franck Boidin, who previously led the French national team. Did he have a big impact on the Japanese team?

He absolutely did. The first thing Boidin said after observing our training was, "You're like pandas. You've got the skills, but you lack the spirit to fight." He told us to transform from pandas into tigers. And it's true. Japanese athletes tend to be quiet and reserved, even during matches. Boidin pushed us, urging us to raise our voices and yell. He taught us that even with great technique, you won't win unless you can intimidate your opponent. You need both technique and spirit to reach the top. I had always been a more defensive fencer, but Boidin's philosophy inspired me to shift to a more aggressive style. Another major influence was assistant coach Chieko Sugawara, who represented Japan at the Athens, Beijing, and London Olympics. Drawing from her experience as a national team athlete, she supplied the team with invaluable advice. Striving to surpass such a decorated fencer became a great source of motivation for us.

© Japanese Fencing Federation

After I wasn't selected for the Tokyo Olympics, there was a time when I seriously considered quitting fencing. But in retrospect, that struggle allowed me to discover what "good fencing" means to me.

- We heard that you analyzed the data of every athlete from each country before the Paris Olympics.

That's right. In Japan, domestic competitions may have hundreds of participants, but if I remember correctly, there were only 34 female foil competitors from eight countries in Paris. With such a small number, it was feasible for me to analyze the data related to each athlete's fighting style. I saved the data to my phone and planned strategies for each opponent. I even scribbled notes onto my hand so I could keep important points in mind during my matches.

- This last August, you won bronze at the women's team foil match in Paris, edging out your opponents in a nail-biting finish. This marked the first Olympic medal ever for Japan's women's fencing, in both individual and team events.

To be perfectly honest, I was thrilled with the result. Joining the parade down Champions Park in front of the Eiffel Tower as a medalist is a memory that will stay with me forever. That said, I regret not performing better in the individual event, and I still wish we had won gold as a team. Overseas competitions will continue throughout the summer, but my new journey has already begun—with my sights set on winning both individual and team gold at the Los Angeles Games four years from now. As younger talent emerges in Japan, I aim to defend my number-one title in Asia while continuing to hone my skills on the world stage.

© Japanese Fencing Federation

Making Fencing More Accessible for All

- Since the women's foil team's medal win, interest in fencing has been growing in Japan.

Competing in the Olympics made me realize just how extraordinary the event is and how much global attention it attracts. The level of fencing in Japan, both men's and women's, has improved dramatically over the past few years, and I hope this trend of support for the sport continues. Viewers may notice that Japanese athletes tend to be smaller and have shorter reach compared to their European counterparts. As larger athletes emerge among the younger generation, Japan will be able to deliver even more thrilling performances worldwide.

Fencing is incredibly fast-paced, and in events like foil—where only the attacker with priority earns points—the rules can be hard to grasp just by watching. To help more people appreciate the highlights and tactical exchanges in fencing, we'll need to make better use of visual technologies to make the sport easier to follow. I hope that by the time of the next Olympics, fencing can become as exciting and accessible to watch as sports like figure skating or shogi on TV.

- A video of you speaking fluent English during an interview with foreign media was shown on television. Are you good with languages?

Not at all! But somehow I ended up being the foreign media spokesperson for the Japan women's national team (laughs). Honestly, it made me realize how much more I need to study. I want to improve my English before the Los Angeles Games.

- Could you say a few final words to current students?

My student life at Keio revolved around fencing, but for most students, those four years are a kind of moratorium—a rare period in life where you can use your time as you see fit. It's a valuable period when you can try anything, whether it be academics, hobbies, or sports. The ability to try new things without fear of failure is one of the great privileges of student life. I hope you'll make the most of that privilege.

I also hope you'll develop the habit of engaging in sports and other physical activity. Even if you're not athletic, why not start by cheering for Keio sports, like the Waseda-Keio matches? As an athlete, I want to share the joy of sports with as many people as possible.

University is also a place to meet friends through your studies, hobbies, or sports. When I talk to Keio alumni, they all say that their friends from university are friends for life. I felt that firsthand when I celebrated in Paris with my friends from high school and university who came all the way to support me at the Olympics.

- Thank you for your time.

Karin Miyawaki

Fencing (Foil)

Miyawaki graduated from the Faculty of Economics in 2019. She began fencing at the age of five, winning a national championship in fourth grade before going on to compete internationally throughout junior high school and beyond. As a student at Keio Girls Senior High School, she first set her sights on competing at the Olympics. Though she missed selection for the Rio 2016 and Tokyo 2021 Olympics, she was chosen for both individual and team events at Paris 2024, earning Japan's first women's Olympic medal in fencing. Now affiliated with Mitsubishi Electric Corporation, she continues to travel the world, training and competing toward her goal of winning gold—individually and as a team—at the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics.

*This article originally appeared as a special feature in the 2025 Winter edition (No. 325) of Juku.

Footer start

Navigation start