Header start

- Home

- Keio Times Index

- Keio Times

Content start

The World Expo Through the Eyes of Yukichi Fukuzawa

Dec. 25, 2025

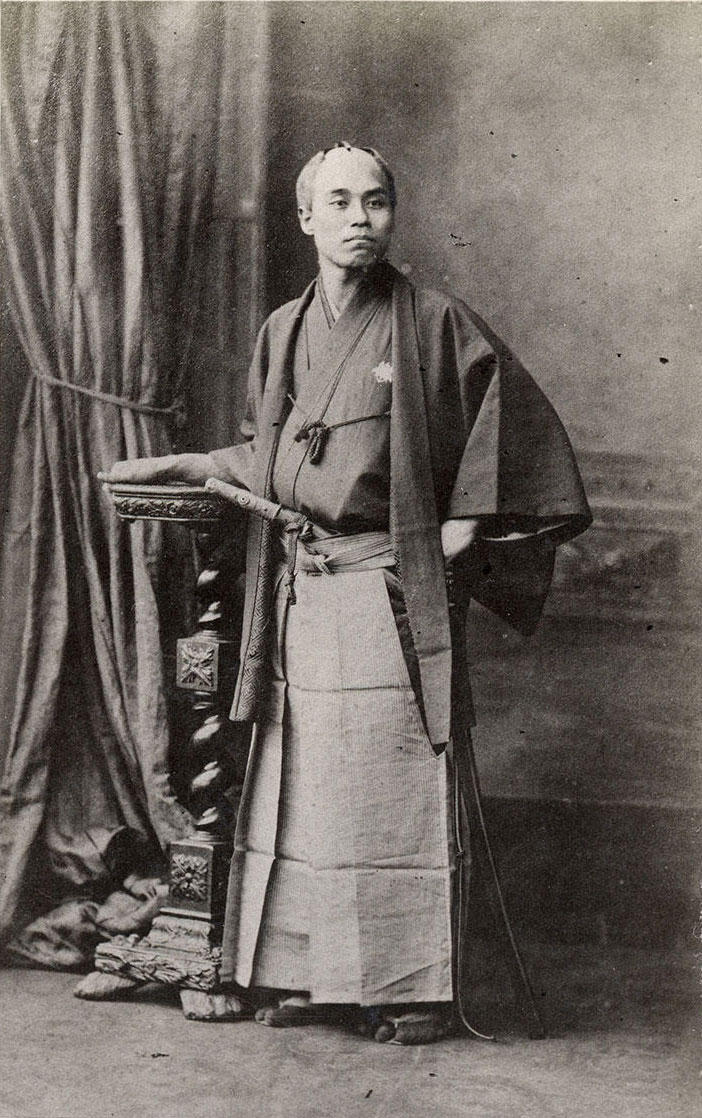

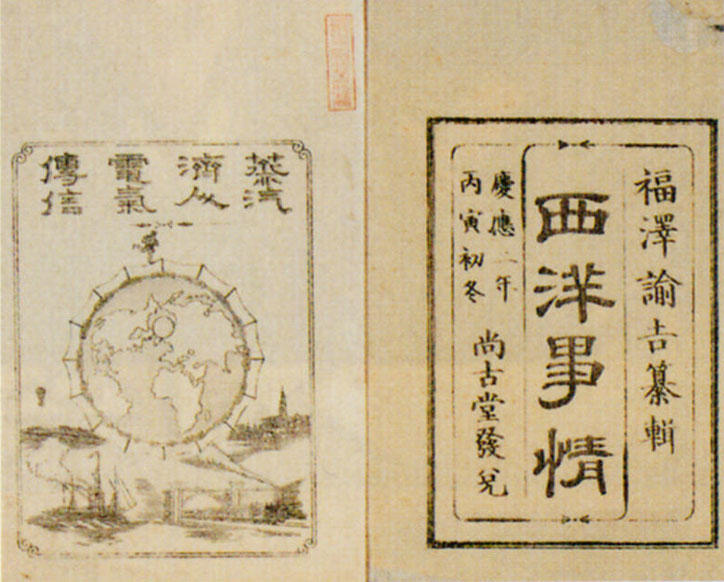

In 1867, during the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate, Yukichi Fukuzawa traveled to England as part of an official Japanese delegation and visited the Great London Exposition, which happened to be underway at the time. Upon his return, Fukuzawa described his firsthand experience of the world's fair and its spirit of open cultural exchange in his book Things Western. How has the spirit Fukuzawa saw there been passed down into the present, and what does it hold for the future? Now that the Osaka–Kansai Expo has come to a close after drawing visitors from around the world, we take a fresh look at its significance.

How Yukichi Fukuzawa Introduced

the Expo’s Impact to Japan

The history of the World Expo, with its participation by many nations around the globe, began in 1851 at the exhibition held in London's Hyde Park. The United Kingdom then hosted the Great London Exposition in 1862, during which a delegation from the Tokugawa shogunate traveled to England and visited the world's fair, marking Japan's first encounter with a world's fair.

Fukuzawa, who served as an interpreter for the delegation, was deeply impressed by the overwhelming power and civilization of the British Empire he witnessed there. In the first volume of Things Western, written after his return to Japan, he described its success and explained that it was not a mere spectacle, but a forum for presenting new technologies and products to the world—an event vital to cultural exchange and technological innovation. He further wrote that expositions exist for mutual teaching and learning, through which participants take the strengths of others and make them their own. He characterized the world's fair as a "trade in intellect and ingenuity," underscoring the importance of learning across borders.

Japan's Evolving Relationship

with the Expo

In 1867, the year after Things Western was published, Japan made its first appearance at the Paris Exposition, with the Tokugawa shogunate and, separately, the Satsuma and Saga domains mounting their own displays. There, Japanese ceramics, lacquerware, washi paper, and artworks such as ukiyo-e captivated European audiences and are said to have sparked the spread of Japanese culture worldwide, including the rise of Japonisme.

More than one century and two world wars would pass before an Expo was held in Japan. In 1970, Asia's first Expo was held in Osaka under the theme "Progress and Harmony for Mankind," the same city that was coincidentally home to Tekijuku, the school where a young Fukuzawa had studied the ways of the West, a field known contemporarily as rangaku (lit. "Dutch studies"), under renowned physician and scholar Ogata Koan. Bringing together the era's most advanced technologies and cultures, the Expo came to symbolize Japan's postwar recovery and growth, the very aspirations of what is often called the Japanese economic miracle.

Since entering the 21st century, Japan has hosted Expo 2005 in Aichi under the theme "Nature's Wisdom," and, now, twenty years later, welcomed the Expo's return to Osaka. What significance can we find in hosting an Expo today?

The Relevance of

"Trade in Intellect and Ingenuity"

in the Present Day

The theme of this year's Osaka–Kansai Expo was "Designing Future Society for Our Lives." As symbolized by its sub-themes—"Saving Lives," "Empowering Lives," and "Connecting Lives"—the Expo aimed to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs and to present ideas and technologies for addressing the challenges of future society. Under the concept of a "laboratory for future society," it sought to gather the world's collective wisdom, including cutting-edge technologies, and to serve as a platform for creating and sharing new ideas to address global challenges.

In Things Western, Fukuzawa observed that technology advances daily and stressed the need to keep acquiring new knowledge. In the same spirit, modern Expos are held to showcase the latest innovations to the world and to contribute to the progress of humanity as a whole. Rather than merely viewing exhibits, visitors from around the world actively exchange ideas, creating opportunities for the "co-creation" of a future society, among the defining features of this World Expo.

The form of the World Expo has evolved with the times. Yet at its core, the "trade in intellect and ingenuity" that Fukuzawa identified has clearly been passed down, taking shape today as a more advanced form of "co-creation." The visitors to this year's Expo must have sensed this spirit in the way people from around the world came together to share their wisdom.

The exchange of knowledge fostered by the Expo, a tradition dating back to Fukuzawa's era, continues to empower us to create a new future for ourselves. If Fukuzawa, who was deeply moved by the Great London Exposition 163 years ago, were to learn of the many ways Keio University's researchers, alumni, and students took part in and contributed to the Osaka–Kansai Expo, what feelings would he have—and what might he have to say? Indulging in that kind of science-fiction fantasy is all part of the fun in reflecting on the World Expo and its relevance today.

*This article appeared in Stained Glass in the 2025 Autumn edition (No. 328) of Juku.

Footer start

Navigation start