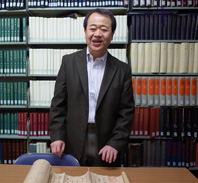

Professor Toru Ishikawa, Faculty of Letters, Tracing the History of Nara-ehon and Emaki through Handwriting

*Position titles, etc., are those at the time of publishing.

Toru Ishikawa

Professor Toru Ishikawa graduated in 1983 from the Faculty of Letters at Keio University, where he subsequently received a master’s degree from the Graduate School of Letters in 1985 and completed doctoral course requirements in 1988. After joining Keio’s Faculty of Letters as a faculty member, he was appointed Associate Professor and has been serving as a Professor since 2005. He received the Nihon Koten Bungaku-kai award (a Japanese classical literature award) in 1993. He specializes in monogatari and setsuwa prose forms of the Heian period to the modern era and his recent research centers on Nara-ehon and emaki with a particular focus on the authors and period of production. His publications include Keio Gijuku Toshokan Shozo Zukai Otogizoshi (Otogizoshi in the Keio University Library collection, Keio University Press), Nara-ehon Emaki no Seisei (The development of Nara illustrated books and handscrolls, Miyai Shoten), and Nyumon Nara-ehon Emaki (Introduction to Nara-ehon and emaki, Shibunkaku).

The Origin of the Name, Nara-ehon

──This is the first time I have heard of Nara-ehon.

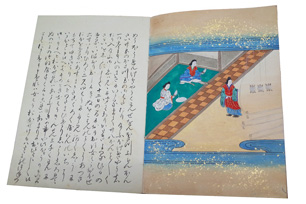

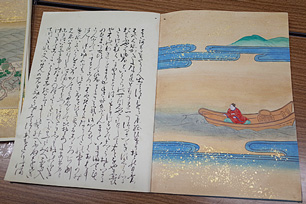

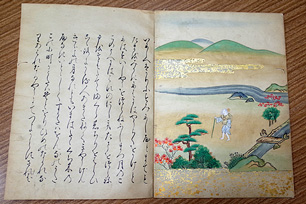

Nara-ehon are illustrated books produced in Kyoto from the Muromachi to the middle of the Edo period and were mainly commissioned by daimyo families. Many people assume that since the genre is called Nara-ehon, the picture books were made in the Nara period or in the region of Nara, but both assumptions are incorrect. The themes include stories like “Urashima Taro” and “Issunboshi,” which are still widely read in Japan today, and they are adorned with beautiful illustrations—thus making many of these books of great artistic value. However, Nara-ehon and emaki have not been the subject of comprehensive research, and even who, when, and how they were created are not well known. That is why I decided to focus on this area of research and shed light on various aspects of this literary genre.

──Why are they called Nara-ehon, when they are not from the Nara period or the region?

Pictures unique to Nara prefecture that you see on popular souvenirs such as folding fans and akahada-yaki pottery are known as Nara-e (Nara pictures). These items were popularized in the Meiji period as gifts purchased by visitors to the region and were known as Nara-e sensu (folding fans) and Nara-e no chawan (bowls). From this period, any pictures that resembled the motifs on these souvenirs were broadly referred to as Nara-e, and the general term Nara-ehon. was given to books with such illustrations. There is no evidence that the word Nara-e was used in the Edo period. Similar types of books were in existence from a very early date, but it is thought that the term Nara-ehon was coined in the modern era.

Nara-ehon are Highly Regarded Artworks

──What made you become interested in Nara-ehon?

Since graduate school I have been researching otogizoshi. They are mostly handwritten copies of stories, and for example, if we look at “Urashima Taro” alone, the story appears in many narrative versions. In other words, the core plot in each handwritten copy may be the same, but the details can vary greatly. Manuscripts that were never reproduced in print are believed to be the original version and are stored in libraries and museums. I transcribe by hand, as necessary, these original works that were never reproduced or made public. Through repeating this process, I began to notice that some of the handwriting seemed familiar from books I had seen before. Before I knew it, I had built up a memory bank of hand-written characters and illustrations. This is how my interest in the content of illustrated books expanded to my research on the actual handwriting and accompanying illustrations.

When you study handwriting, you need to take photos as proof to back up your argument. It was not easy back when I started research in this area as only film cameras were available, and photo processing cost time and money. Later the influx of digital technology, which made processing of images possible on the camera and the computer, allowed for detailed comparison and categorization of handwriting, and I was able to make remarkable progress in my research.

During that time in 1996, when Keio University acquired a copy of the Gutenberg Bible, a project was launched at Keio to digitize copies of the Gutenberg Bible in collections around the world along with other rare historical books. In 2001, another project got underway to digitize Nara-ehon and emaki, and I travelled around the world in search of such materials, including those kept in the British Museum and the Chester Beatty Library in Ireland, and I spent a few years archiving them for our digital collection.

──Are there collectors of Nara-ehon overseas as well?

There was a significant outflow of Nara-ehon from Japan. However, as the genre itself is not well known, in a lot of the cases they are stored away under the generic category of Japanese works of art, and very often there is no way of knowing what kind of illustrated scrolls they are until you actually see them. Representative among Japanese art overseas is ukiyo-e, or pictures of the floating world. Ukiyo-e prints were produced cheaply and in great number using woodblocks during the second half of the Edo period, allowing it to spread its influence beyond Japan. In comparison to this, as Nara-ehon were made by hand, one by one, they were produced in a smaller quantity and did not get the recognition that ukiyo-e achieved. However, like uki-yo-e prints, Nara-ehon are extremely beautiful, and because they were handmade, visitors to Japan must have seen their artistic value and taken them back to their home country.

I recently investigated a collector of emaki, whose collection is currently stored at the Unterlinden Museum in Germany. He was a German doctor named Erwin Bälz who arrived in Japan as an oyatoi (Japan’s foreign employees) in the Meiji period. He married a Japanese woman and spent many years in Japan before returning to Stuttgart, where he lived the rest of his life. After his death his collection was donated to the Linden-Museum Sttutgart, Garmany. Last year I also made a trip to Prague to visit a wealthy American gentleman, who I had heard had in his possession a magnificent emaki. He had in fact a Shuten-doji emaki, which was once a part of William Bigelow’s collection. Bigelow, alongside Tenshin Okakura and Ernest Fenellosa, did much to contribute to the development of modern Japanese art, and a large part of his collection was donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. However, he had entrusted to a close friend his most precious work, which was this Shuten-doji emaki. From this perspective, studying Nara-ehon and emaki offers a glimpse into the various exchanges that had taken place between Japan and other countries in the world in the modern era.

Japan’s First Female Illustrated Book Author and Artist, Tsuna Isome

──You have made many discoveries about Nara-ehon. Can you tell us about what they were?

Firstly, I have begun to unearth information on the authors and periods of production of Nara-ehon and emaki through my research on handwriting. For example, in 2001, I discovered the handwriting of Ryoi Asai in a Nara-ehon/emaki. In a copy of “Genpei Josuiki,” I came across Ryoi Asai’s name, or more precisely the pseudonym that he had adopted during that time, and the year in which the work was completed. Asai is a well-known writer of kaidan ghost tales from the first half of the Edo period and has been the focus of much research. Some researchers were adamant that a famous writer of that caliber would not have produced Nara-ehon or emaki. However, I was able to prove otherwise with the discovery of the autographed copy of “Genpei Josuiki.” Now that we know Asai was involved in the production of Nara-ehon, this naturally tells us more about the general period and area in which they were made.

In 2008, I discovered the handwriting of Tsuna Isome. There was an exhibition of an Ise monogatari emaki at Jissen Women’s University, where I was teaching at the time, and the writing and illustration looked exactly like those of the Ise monogatari emaki that I owned. Along with the exhibited work was a photo of the autograph “Work by Isomeshi Musume.” This helped me to identify the person that was behind the production of a great many Nara-ehon and emaki works. On top of that, it was generally perceived that the production of Nara-ehon and emaki was done by men who were allocated different tasks, but this discovery showed that one woman had taken up both tasks from writing to illustrating. As this took place in the first half of the Edo period, this would make her Japan’s first female author and artist of illustrated books. As I researched Isomeshi Musume, I found out that she was an Edo-period writer named Tsuna Isome, who also produced oraimono textbooks for women. And because both Asai and Isome were from Kyoto, we now know that Nara-ehon were produced in Kyoto in the 1600s.

──It is very surprising to learn that famous writers of that time were involved in the production of Nara-ehon.

This is not all, I made another very interesting discovery in a preface to one of Asai’s posthumous ghost tale work “Inuhariko.” The publisher had written, “By the hand of Ryoi Asai.” The work is thought to be a block printed book, in which the handwriting of Asai was carved into the surface of a block of wood. During that period, there were professional craftsmen who worked as copyists. Writers were not necessarily skilled at handwriting, so these copyists would produce the writing on a thin piece of paper, which was then affixed to a woodblock and used as the basis for the carving. However, Asai had beautiful handwriting, which allowed him to work both as a writer and a copyist.

I had already known this, but one day I found the same handwriting from “Inuhariko” in a Nara-ehon/emaki. This led me to think that Asai’s original occupation may have been a copyist. He read a great number of works through his work as a scribe, which helped his grounding as a writer, and once he became a writer, he at times transcribed some of his own works. It is now an accepted theory that if a block printed book has Asai’s handwriting, it was also written by him. I am not a specialist in Ryoi Asai, but gathering Nara-ehon and emaki materials and comparing the handwriting leads to research on the authors and the literary content.

──So, recent advances in this research field have led to the re-evaluation of the Nara-ehon genre.

The genre is finally receiving the recognition it deserves, and in a certain sense, research in this area has only just begun, as so many materials have not been brought to light. Fortunately, Japanese people tend to take great care of books, so anyone can easily buy an Edo-period book from a second-hand bookstore. There are so many Nara-ehon and Japanese literary works lying dormant and hidden among these stacks of old books.

In addition, research on Nara-ehon and emaki as literary works rather than artworks has only just begun. I would like to continue my ongoing research on otogizoshi, and through my research on Nara-ehon, shed more light on the historical background, as well as spread basic knowledge, of Japanese literature. Like mystery novels, I find great satisfaction in solving puzzles, so as I continue my efforts to verify facts in literary history, I am also looking forward to more exciting and surprising discoveries.

*This article appeared in "Kenkyu Saizensen" (January 21, 2016) of Keio University Japanese Website.

*Position titles, etc., are those at the time of the interview.